TL;DR: Server-Sent Events (SSE) is a standard that enables Web servers to push data in real time to clients. In this article, we will learn how to use this standard by building a flight timetable demo application with React and Node.js. However, the concepts you will learn following this tutorial are applicable to any programming language and technology. You can find the final code of the application in this GitHub repository.

“Learn how to build real-time web applications with the Server-Sent Events protocol.”

Tweet This

Introducing on Server-Sent Events

The typical interactions between browsers and servers consist of browsers requesting resources and servers providing responses. But, can we make our servers send data to clients at any time without explicit requests?

The answer is yes! We can achieve that by using Server-Sent Events (which is also known as SSE or Event Source), a W3C standard that allows servers to push data to clients asynchronously. This may suggest using that annoying polling we'd implement to get the progress status from a long server processing but, thanks to SSE, we don't have to implement polling to wait for a response from the server. We don't even need any complex and strange protocol. That is, we can continue to use the standard HTTP protocol.

So, let's take a look at how to use Server-Sent Events in a realistic application.

Building a Real-Time App with Server-Sent Events

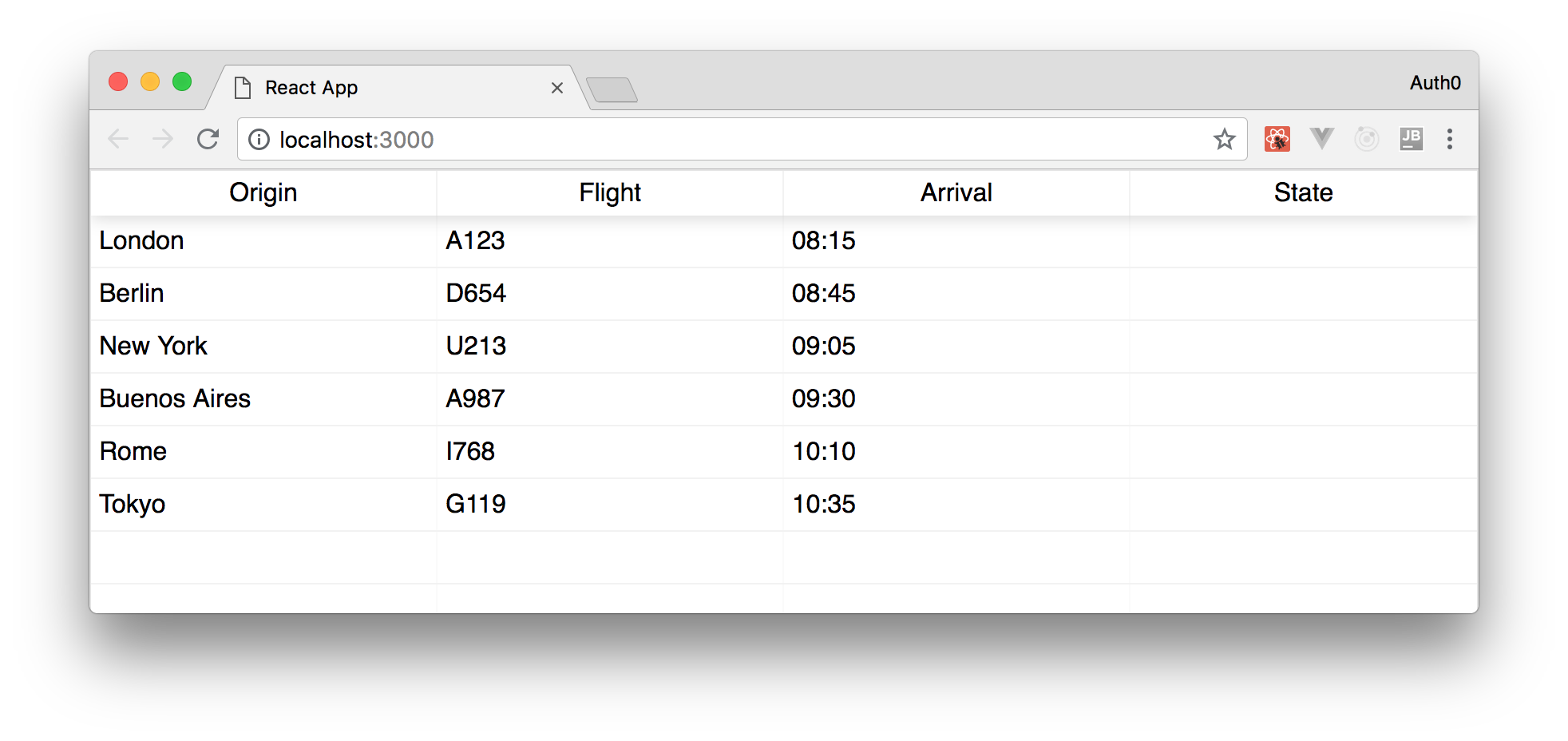

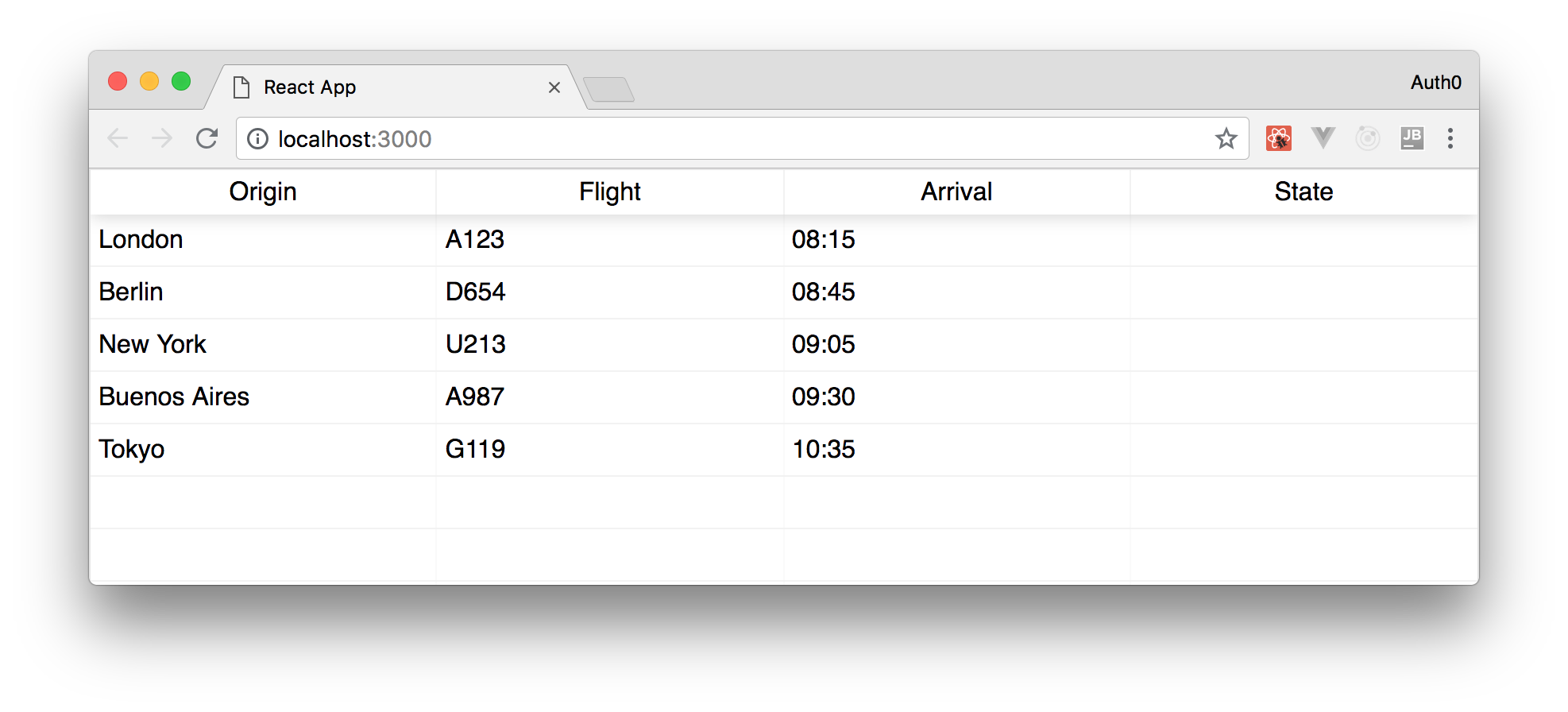

In order to learn how to use Server-Sent Events, we are going to develop a simple flight timetable application (similar to those flight trackers you can find at any airport). The timetable app will consist of a simple web page showing a list of flights as shown in the following picture:

Through this real-time app, we can find the flight arrival timetable and, after implementing Server-Sent Events, we will see automatically updates when the state of flights change. In our demo application, we are going to simulate the flight state changes using scheduled events. However, one can easily replace this mechanism with more realistic ones on production-ready applications.

So, let's start coding and discover how the Server-Sent Events standard works.

Scaffolding a React Application

As the first step, let's scaffold our React client application. To make things simple, we will use

to set up our React-based client. So, let's make sure that we have Node.js installed on our machine and let's type the following command in a terminal window:create-react-app

# installing create-react-app globally npm install -g create-react-app

After installing

create-react-appcreate-react-app real-time-sse-app

After a few seconds, we will get a new directory called

real-time-sse-appsrcSince our application will show data in a tabular form, we will install a React component that simplifies the task of rendering data into tables: React Table. To add this component to our application, we will type the following commands in our terminal:

# make sure we are on the React app project root cd real-time-sse-app # then install the React Table dependency npm install react-table

Now, we are ready to start changing the application code. So, let's open the

App.jssrc// src/App.js import React, { Component } from "react"; import ReactTable from "react-table"; import "react-table/react-table.css"; import { getInitialFlightData } from "./DataProvider"; class App extends Component { constructor(props) { super(props); this.state = { data: getInitialFlightData() }; this.columns = [ { Header: "Origin", accessor: "origin" }, { Header: "Flight", accessor: "flight" }, { Header: "Arrival", accessor: "arrival" }, { Header: "State", accessor: "state" } ]; } render() { return ( <div className="App"> <ReactTable data={this.state.data} columns={this.columns} /> </div> ); } } export default App;

Here, we are importing the stuff we need to set up the flight timetable. In particular, in addition to standard React basic elements, we are importing the

ReactTablegetInitialFlightDataDataProviderAppstateIn the constructor, we also define the table's structure by mapping flight properties to table columns. As we can see, this mapping consists of an array of objects like the following:

this.columns = [ { Header: "Origin", accessor: "origin" }, { Header: "Flight", accessor: "flight" }, { Header: "Arrival", accessor: "arrival" }, { Header: "State", accessor: "state" } ];

As defined above, each flight object contains a

HeaderaccessorHeaderaccessorFinally, within the

renderAppReactTableNow, within the

srcDataProvider.js// src/DataProvider.js export function getInitialFlightData() { return [ { origin: "London", flight: "A123", arrival: "08:15", state: "" }, { origin: "Berlin", flight: "D654", arrival: "08:45", state: "" }, { origin: "New York", flight: "U213", arrival: "09:05", state: "" }, { origin: "Buenos Aires", flight: "A987", arrival: "09:30", state: "" }, { origin: "Rome", flight: "I768", arrival: "10:10", state: "" }, { origin: "Tokyo", flight: "G119", arrival: "10:35", state: "" } ]; }

The module above exports the

getInitialFlightDataSo far, our application presents the flight data in tabular form. Let's check it out in a web browser! To run the app, type the following command in the terminal:

# from the real-time-sse-app, start the React app npm start

After a few seconds, we should see in the browser the list of flights as shown in the picture above. If the browser doesn't open automatically, please open it and go to

.http://localhost:3000

Note: For some unknown reason, the application fails to start, issuing

from thenpm idirectory might solve the problem.real-time-sse-app

Consuming Server-Sent Events with React

After making our React application present some static data, let's add the functionality it needs to consume server-side generated events.

To do this, we are going to use the

API, a standard interface created to interact with the Server-Sent Events protocol. As MDN documentation says, "an EventSource

instance opens a persistent connection to an HTTP server, which sends events in EventSource

format. The connection remains open until closed by calling text/event-stream

"EventSource.close()

So, as the first step, let's add the

eventSourceAppEventSource// src/App.js // ... import statements ... class App extends Component { constructor(props) { // ... super, state, and columns ... this.eventSource = new EventSource("events"); } // ... render ... } export default App;

The

EventSource()In our case, the client expects a stream of events from the

eventshttp://localhost:3000http://localhost:3000/eventsNow, let's capture events sent by the server by adding a few lines of code. We are going to add a new method called

updateFlightStateAppApp// src/App.js // ... import statements ... class App extends Component { // ... constructor ... componentDidMount() { this.eventSource.onmessage = e => this.updateFlightState(JSON.parse(e.data)); } updateFlightState(flightState) { let newData = this.state.data.map(item => { if (item.flight === flightState.flight) { item.state = flightState.state; } return item; }); this.setState(Object.assign({}, { data: newData })); } // ... render ... } export default App;

As we can see, we added an event handler to the

onmessageeventSourcecomponentDidMount()onmessageupdateFlightState()statee.dataAlthough we can't test the application yet (we still have to create our backend and send events from it), our React application is now ready to handle server-sent events. Not hard, huh?

Building Real-Time Backends with Server-Sent Events

The server-side of our application will be simple Node.js web server that responds to requests submitted to the

eventsreal-time-sse-backendreal-time-sse-appserverserver.js// server.js const http = require("http"); http .createServer((request, response) => { console.log("Requested url: " + request.url); if (request.url.toLowerCase() === "/events") { response.writeHead(200, { Connection: "keep-alive", "Content-Type": "text/event-stream", "Cache-Control": "no-cache" }); setTimeout(() => { response.write('data: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}'); response.write("\n\n"); }, 3000); setTimeout(() => { response.write('data: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landed"}'); response.write("\n\n"); }, 6000); } else { response.writeHead(404); response.end(); } }) .listen(5000, () => { console.log("Server running at http://127.0.0.1:5000/"); });

At the beginning of the file, we import the

httpcreateServer/eventsIn fact, the

keep-aliveConnectionThe

text/event-streamContent-TypeFinally, the

Cache-ControlAfter sending these headers, the client using the

EventSource()data: xxxxxxx

The

xxxxxxxdata: This is a message\n data: A long message\n \n \n

In order to execute the web server we created so far, let's type the following commands on the terminal:

# make sure we are in the real-time-sse-backend directory cd real-time-sse-backend # run the server node server.js

Consuming Server-Sent Events

After building both our React client and our Node.js server, we want to make them communicate with each other. However, they run on different domains. Currently, the React client is running on

http://localhost:3000http://localhost:5000This means that, if we don't do anything, our React client won't be able to issue HTTP requests to the Node.js server due to the same-origin policy applied by the browser itself.

We could get around the problem by simply adding a

proxypackage.jsoncreate-react-appSo, in order to enable communication between our client app and our backend server, we need to make our server support CORS (Cross-origin resource sharing). With this approach, the server authorizes a client published on a different domain to request its resources. To enable CORS in our Node.js server, we can simply add a new header to be sent to the client: the

Access-Control-Allow-Originresponse.writeHeadresponse.writeHead(200, { Connection: "keep-alive", "Content-Type": "text/event-stream", "Cache-Control": "no-cache", "Access-Control-Allow-Origin": "*" });

The asterisk assigned to the

Access-Control-Allow-OriginOnce we have enabled CORS on the Node.js server, we should change the URL passed to the

EventSource()./src/App.jsthis.eventSourcethis.eventSource = new EventSource("http://localhost:5000/events");

Bingo! If we run our backend server again and then launch the client application, after a few seconds, we will see our browser showing our real-time application.

As a recap, this is how we run our projects:

# from the backend directory cd real-time-sse-backend # start the Node.js server node server.js # and from the real-time-sse-app directory cd real-time-sse-app # start the React application npm start

Note: It might be easier to run both applications from different terminal sessions. Otherwise, we might have to run the backend server in the background by issuing

.node server.js &

Managing Event Types with Server-Sent Events

The timetable application that we have developed so far responds to server events always in the same way: by updating a specific flight sent in the event's

dataSuppose, for example, that we want to remove the row that describes a flight after a certain amount of time that this flight landed. How could the server send an event that is not a state change? How can the client capture an event saying that it should remove a row from the table?

We could think of using the

dataevent// server.js const http = require("http"); http .createServer((request, response) => { console.log("Requested url: " + request.url); if (request.url.toLowerCase() === "/events") { response.writeHead(200, { Connection: "keep-alive", "Content-Type": "text/event-stream", "Cache-Control": "no-cache", "Access-Control-Allow-Origin": "*" }); setTimeout(() => { response.write("event: flightStateUpdate\n"); response.write('data: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}'); response.write("\n\n"); }, 3000); setTimeout(() => { response.write("event: flightStateUpdate\n"); response.write('data: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landed"}'); response.write("\n\n"); }, 6000); setTimeout(() => { response.write("event: flightRemoval\n"); response.write('data: {"flight": "I768"}'); response.write("\n\n"); }, 9000); } else { response.writeHead(404); response.end(); } }) .listen(5000, () => { console.log("Server running at http://127.0.0.1:5000/"); });

While defining the response, we added a new

eventdataeventflightStateUpdateflightRemovaleventAs such, we are saying to our client that some events must update flights' state (e.g. from

landinglandedAfter refactoring our backend server, we will need to update our client application to handle these different types of event. So, let's open the

src/App.js// src/App.js // ... import statements ... class App extends Component { // ... constructor ... componentDidMount() { this.eventSource.addEventListener("flightStateUpdate", e => this.updateFlightState(JSON.parse(e.data)) ); this.eventSource.addEventListener("flightRemoval", e => this.removeFlight(JSON.parse(e.data)) ); } removeFlight(flightInfo) { const newData = this.state.data.filter( item => item.flight !== flightInfo.flight ); this.setState(Object.assign({}, { data: newData })); } // ... render, updateFlightState ... } export default App;

As we can see, the body of the

componentDidMount()onmessageaddEventListener()In the example, we assigned the

updateFlightState()flightStateUpdateremoveFlight()flightRemovalIf we run both our projects again and open our React application on a browser (

), after 9 seconds (as defined in the last http://localhost:3000/

setTimeoutserver.jsHandling Connection Closure on Server-Sent Events

The Server-Sent Event connection between the client and the server is a streaming connection. This means that the connection will be kept active indefinitely unless the client or the server stops running. If our server has no more events to send or the client isn't longer interested in server's events, how can we explicitly stop the currently active connection?

Let's consider the case where the client wants to stop the event stream. To learn about this, let's create a button that allows the user to stop receiving new events. So, let's change the

render()Apprender() { return ( <div className="App"> <button onClick={() => this.stopUpdates()}>Stop updates</button> <ReactTable data={this.state.data} columns={this.columns} /> </div> ); }

Here we added a

<button>stopUpdates()stopUpdates() { this.eventSource.close(); }

In other words, to stop the event stream, we simply invoked the

close()eventSourceClosing the event stream on the client doesn't automatically closes the connection on the server side. This means that the server will continue to send events to the client. To avoid this, we need to handle the connection close request on the server side. We can do it by adding an event handler for the

close// server.js const http = require("http"); http .createServer((request, response) => { console.log(`Request url: ${request.url}`); request.on("close", () => { if (!response.finished) { response.end(); console.log("Stopped sending events."); } }); // ... etc ... }) .listen(5000, () => { console.log("Server running at http://127.0.0.1:5000/"); });

The

request.on()closeresponse.end()Since our server event generators are scheduled by using

setTimeout()setTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { response.write("event: flightStateUpdate\n"); response.write('data: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}'); response.write("\n\n"); } }, 3000);

Note: We have to implement the same strategy for the other timeout events.

Now, when we need to close the connection from the server, we will need to invoke the

response.end()To achieve that, an easy strategy to follow is to create a specific type of event that informs the client that they have to close the connection. For example, our server could simply generate a

closedConnectionsetTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { response.write("event: closedConnection\n"); response.write("data: "); response.write("\n\n"); } }, 3000);

Then, to handle this event on our React application, we could update our

src/App.js// src/App.js // ... import statements ... class App extends Component { // ... constructor ... componentDidMount() { // ... flightStateUpdate and flightRemoval event handlers ... this.eventSource.addEventListener("closedConnection", e => this.stopUpdates() ); } // ... updateFlightState and removeFlight methods ... stopUpdates() { this.eventSource.close(); } // ... render ... } export default App;

As we can see, handling this new event type is as easy as assigning the

stopUpdates()closedConnectionHandling Connection Recovery on Server-Sent Events

So far, we built a real-time application based on Server-Sent Events that is quite complete. We are able to get different types of events pushed by the server and to control the end of the event stream. But, what happens if the client loses some event due to network issues? Of course, it depends on the specific application. In some situations, we may ignore the loss of some event, in some others we can't.

Let's consider, for example, the event stream we implemented. If a network issue happens and the client loses the

flightStateUpdateHowever, if the network issue happens immediately after the flight enters in the landing state and the connection is restored after the

flightRemovalThe Server-Sent Events protocol help us by providing a mechanism to identify events and to restore a dropped connection. Let's learn about it.

When the server generates an event, we have the ability to assign an identifier by attaching an

idflightStateUpdatesetTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = 'id: 1\nevent: flightStateUpdate\ndata: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}\n\n'; response.write(eventString); } }, 3000);

Here, we are making a little refactoring to our code to add the

id1When a network issue happens and the connection to an event stream is lost, the browser will automatically attempt to restore the connection. When the connection is established again, the browser will automatically send the identifier of the last received event in the

Last-Event-IdLet's implement this strategy in our server. With a bit of refactoring, the following is the final version of the server side code:

// server.js const http = require("http"); http .createServer((request, response) => { console.log(`Request url: ${request.url}`); const eventHistory = []; request.on("close", () => { if (!response.finished) { response.end(); console.log("Stopped sending events."); } }); if (request.url.toLowerCase() === "/events") { response.writeHead(200, { Connection: "keep-alive", "Content-Type": "text/event-stream", "Cache-Control": "no-cache", "Access-Control-Allow-Origin": "*" }); checkConnectionToRestore(request, response, eventHistory); sendEvents(response, eventHistory); } else { response.writeHead(404); response.end(); } }) .listen(5000, () => { console.log("Server running at http://127.0.0.1:5000/"); }); function sendEvents(response, eventHistory) { setTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = 'id: 1\nevent: flightStateUpdate\ndata: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}\n\n'; response.write(eventString); eventHistory.push(eventString); } }, 3000); setTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = 'id: 2\nevent: flightStateUpdate\ndata: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landed"}\n\n'; response.write(eventString); eventHistory.push(eventString); } }, 6000); setTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = 'id: 3\nevent: flightRemoval\ndata: {"flight": "I768"}\n\n'; response.write(eventString); eventHistory.push(eventString); } }, 9000); setTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = "id: 4\nevent: closedConnection\ndata: \n\n"; eventHistory.push(eventString); } }, 12000); } function checkConnectionToRestore(request, response, eventHistory) { if (request.headers["last-event-id"]) { const eventId = parseInt(request.headers["last-event-id"]); const eventsToReSend = eventHistory.filter(e => e.id > eventId); eventsToReSend.forEach(e => { if (!response.finished) { response.write(e); } }); } }

In the new version of our backend, we introduced an array called

eventHistorycheckConnectionToRestore()sendEvents()Now, we can see that each time an event is sent to the client, it is also stored in the

eventHistorysetTimeout(() => { if (!response.finished) { const eventString = 'id: 1\nevent: flightStateUpdate\ndata: {"flight": "I768", "state": "landing"}\n\n'; response.write(eventString); eventHistory.push(eventString); } }, 3000);

If the

checkConnectionToRestore()Last-Event-IdeventHistoryfunction checkConnectionToRestore(request, response, eventHistory) { if (request.headers['last-event-id']) { const eventId = parseInt(request.headers['last-event-id']); const eventsToReSend = eventHistory.filter((e) => e.id > eventId); eventsToReSend.forEach((e) => { if (!response.finished) { response.write(e); } }); }

With these changes, we make our backend more robust and more resilient.

“Updating the state of frontend applications with Server-Sent Events is quite easy.”

Tweet This

Browser Support for Server-Sent Events

According to

, Server-Sent Events are currently supported by all major browsers but Internet Explorer, Edge, and Opera Mini. Although supporting them in Edge is under consideration, the lack of universal support forces us to use polyfills, such as Remy Sharp's EventSource.js, Yaffle's EventSource, or AmvTek's EventSource.caniuse.com

Using these polyfills is very simple. In this section, we will see how to use AmvTek's polyfill. The process of using the other ones is not so different. In order to add AmvTek's EventSource polyfill to our React client application, we need to install it via

npmnpm install eventsource-polyfill

Then, we should import the module in the

App// src/App.js // ... other import statements ... import 'eventsource-polyfill'; // ... App class definition and export ...

And that's all. The polyfill will define an

EventSourceServer-Sent Events vs WebSockets

Using the Server-Sent Events protocol helps us to solve some common issues that involve waiting for data from the server. So, instead of implementing a long polling, whose main drawback is consuming resources both on the client and on the server side, we get a simple and performant solution.

An alternative approach is to use WebSockets, a standard TCP based protocol providing full duplex communication between the client and the server. What benefits does WebSockets bring with respect to Server-Sent Events? When to use one technology instead of the other?

The following are some considerations to keep in mind when choosing between Server-Sent Events and WebSockets:

- WebSockets support a bidirectional communication, while Server-Sent Events support only communication from the server to the client.

- WebSockets is a low-level protocol, while Server-Sent Events is based on HTTP and so it doesn't require additional settings in the network infrastructure.

- WebSockets supports binary data transfer, while Server-Sent Events supports only text-based data transfer. That is, if we want to transfer binary data via Server-Sent Events we need to encode it in Base64.

- The combination of low-level protocol and support of binary data transfer makes WebSockets more suitable than Server-Sent Events for applications requiring real-time binary data transfer as may happen in gaming or other similar application types.

Read a full comparison between WebSockets and Server-Sent Events (SSE)

Aside: Auth0 Authentication with JavaScript

At Auth0, we make heavy use of full-stack JavaScript to help our customers to manage user identities, including password resets, creating, provisioning, blocking, and deleting users. Therefore, it must come as no surprise that using our identity management platform on JavaScript web apps is a piece of cake.

Auth0 offers a free tier to get started with modern authentication. Check it out, or sign up for a free Auth0 account here!

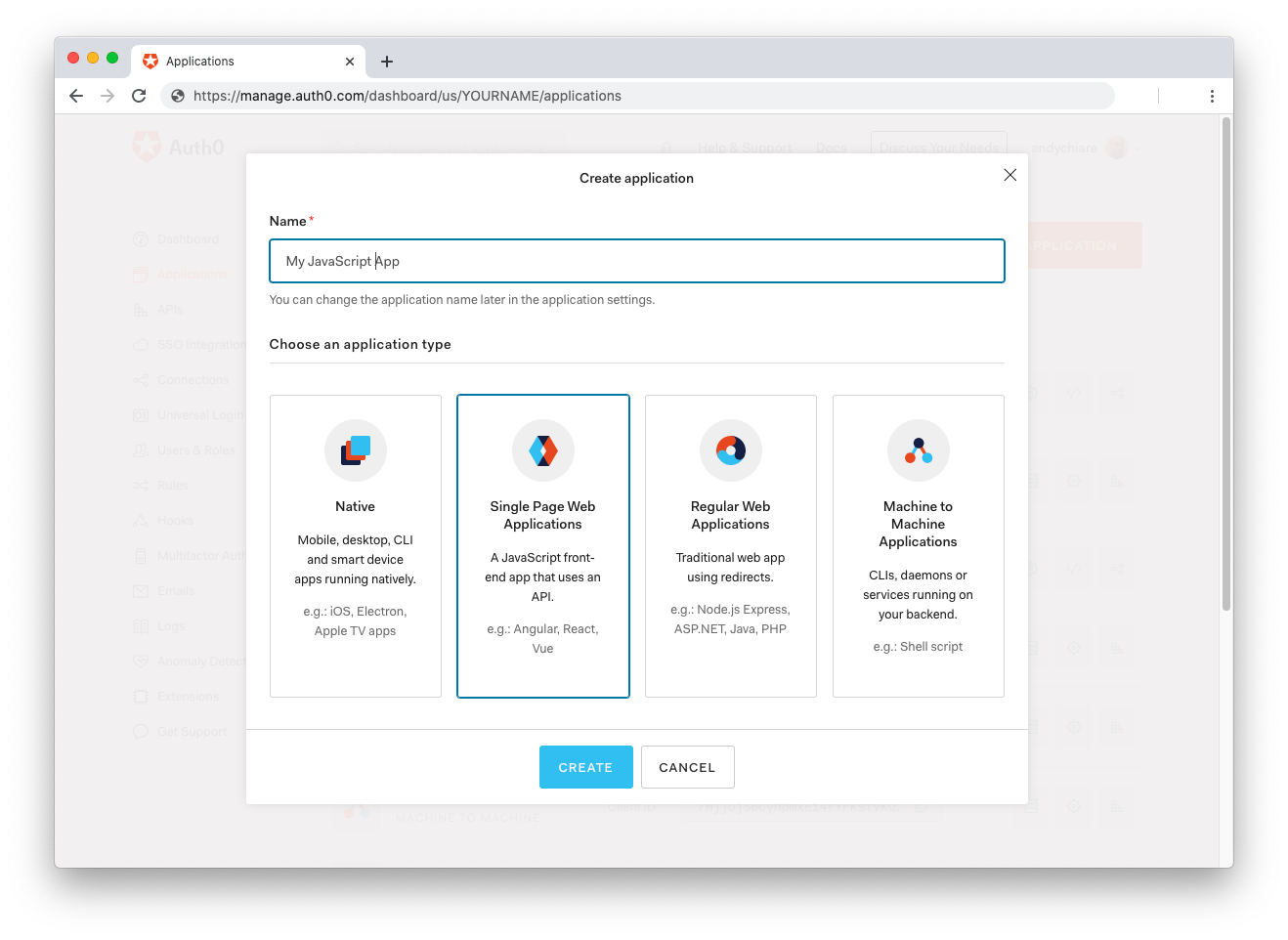

Then, go to the Applications section of the Auth0 Dashboard and click on "Create Application". On the dialog shown, set the name of your application and select Single Page Web Applications as the application type:

After the application has been created, click on "Settings" and take note of the domain and client id assigned to your application. In addition, set the Allowed Callback URLs and Allowed Logout URLs fields to the URL of the page that will handle login and logout responses from Auth0. In the current example, the URL of the page that will contain the code you are going to write (e.g.

http://localhost:8080Now, in your JavaScript project, install the

library like so:auth0-spa-js

npm install @auth0/auth0-spa-js

Then, implement the following in your JavaScript app:

import createAuth0Client from '@auth0/auth0-spa-js'; let auth0Client; async function createClient() { return await createAuth0Client({ domain: 'YOUR_DOMAIN', client_id: 'YOUR_CLIENT_ID', }); } async function login() { await auth0Client.loginWithRedirect(); } function logout() { auth0Client.logout(); } async function handleRedirectCallback() { const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated(); if (!isAuthenticated) { const query = window.location.search; if (query.includes('code=') && query.includes('state=')) { await auth0Client.handleRedirectCallback(); window.history.replaceState({}, document.title, '/'); } } await updateUI(); } async function updateUI() { const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated(); const btnLogin = document.getElementById('btn-login'); const btnLogout = document.getElementById('btn-logout'); btnLogin.addEventListener('click', login); btnLogout.addEventListener('click', logout); btnLogin.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'none' : 'block'; btnLogout.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'block' : 'none'; if (isAuthenticated) { const username = document.getElementById('username'); const user = await auth0Client.getUser(); username.innerText = user.name; } } window.addEventListener('load', async () => { auth0Client = await createClient(); await handleRedirectCallback(); });

Replace the

andYOUR_DOMAINplaceholders with the actual values for the domain and client id you found in your Auth0 Dashboard.YOUR_CLIENT_ID

Then, create your UI with the following markup:

<p>Welcome <span id="username"></span></p> <button type="submit" id="btn-login">Sign In</button> <button type="submit" id="btn-logout" style="display:none;">Sign Out</button>

Your application is ready to authenticate with Auth0!

Check out the Auth0 SPA SDK documentation to learn more about authentication and authorization with JavaScript and Auth0.

Summary

In this article, we used Server-Sent Events to develop a real-time application that simulates a flight timetable. During the development, we had the opportunity to explore the features that the standard provides to support event typing, connection control, and restoring. We also learned how to add support Server-Sent Events on browsers that do not support it by default. Lastly, we took a look at a brief comparison between Server-Sent Events and WebSockets.

If needed, you can check and download the final code of the project developed throughout this article from this GitHub repository.

About the author

Andrea Chiarelli

Principal Developer Advocate

I have over 20 years of experience as a software engineer and technical author. Throughout my career, I've used several programming languages and technologies for the projects I was involved in, ranging from C# to JavaScript, ASP.NET to Node.js, Angular to React, SOAP to REST APIs, etc.

In the last few years, I've been focusing on simplifying the developer experience with Identity and related topics, especially in the .NET ecosystem.